Failure. What a loaded word. What a thing to be avoided. Nobody wants to feel it, but the readings this week have provided some insight into leaning into the possibility, the potential, and ultimately the reality of failure, and perhaps even using failure to grow and develop our pedagogical practices and the learning experience. I do find it somewhat ironic that we are engaging with this concept as we go into our final presentations and project submissions—none of us want to acknowledge that we might “fail” in our final or in the completion of our projects—but I believe that each of us can benefit from some reflection on failure. Not just in the context of our ITP coursework, but upon deeper reflection of our pedagogical practices, the discussion of failure with our students, and also the failure(s) of the larger education landscape.

This semester, we’ve addressed flexibility, multiple modalities, and universal design as important practices to undertake in our pedagogy and I believe thinking these things through and adopting strategies that allow for openness and the unexpected to happen in our coursework is truly beneficial. Nonetheless, we won’t be able to prepare for every possible outcome and will, very likely, fail in some of our pursuits. We will also be part of larger institutional systems that won’t always operate the way we think they should or need them to. For me, the last year in ITP has provided me with a critical lense for my pedagogical practice ensuring that I am always thinking of innovative strategies for teaching and learning, but also to be prepared for the unexpected and for the difficult situations.

I found Allison Carr’s essay, “In Support of Failure” the most compelling of this week’s readings as it provides a framework for defining, feeling, accepting, reflecting on, and using our own failure to create a “pedagogy of failure.” It’s a very personal piece and reminds us that learning, and failure for that matter, are very personal experiences. We’ve all been there–writer’s block, the inability to comprehend or master a concept, failing a test or course, feeling like an imposter in an endeavor we don’t quite feel equipped for. Carr wants us to explore what it means to fail–to fail in our own academic pursuits as students, fail in our pedagogical pursuits as instructors, and to encourage our students to recognize and embrace failure, too.

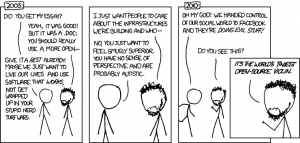

She states: “And though we experience and talk about failure in all realms of life, it is especially prominent in our classrooms, where failure is formalized with rubrics and learning outcomes and complicated metrics of assessment. Yes, ‘failure’ (little f) becomes ‘Failure’ (big f) in our classrooms, the most extensive system of socialization available in the modern world. We are all inculcated into this reductive, do-or-die paradigm. We are entrenched.” She goes on to say, “…failure—more specifically, avoiding failure—is the object around which school is structured.” Yet, aren’t we also told that we should learn from failure? Shouldn’t the classroom be a safe space for trial and error, for attempting new things and to not always know what we are doing (because we don’t)? Learning is an active and iterative practice.

Further, Carr states, “Our classrooms, I hope it is clear, teach us how to feel. More specifically, they teach us how to succeed and how to fail, and with shame deployed as a tool of self-surveillance, it’s clear that our emotional education is intertwined with these more concrete lessons…As an outcome of assessment, failure makes us profoundly aware of our place in social and academic strata. It makes the borders of our physical and emotional selves known to us, and it emphasizes our distance between ourselves and others.” She hopes that a deep study of failure will help one understand the “complex relationship between one’s emotions, one’s identity, and one’s (academic) performance…”

Failure and success are both a part of the learning process. She’s coming at it from a composition instructor’s perspective and her discipline claims that writing is a process, but this ethos can be applied beyond the composition course. Nonetheless, higher education, and education institutions more broadly, are fixated on “product-oriented concept of creative intellectual work” and often overlooks, or doesn’t make room for, the process of it all. By acknowledging and focusing on the very personal experience of failure, Carr brings attention to the humanness of education. Although there are outcomes to be achieved and goals to be attained, critical attention to the process must be present as well.

She proposes a pedagogy of failure that accounts for relationality as well as isolation and would incorporate unpredictability and improvisation, as well as acknowledge the felt experience of creative and intellectual work. She poses the following:

- I want to know what happens when failure isn’t the silent antithesis of success or the final and unspeakable consequence of struggle or deviance against social and/or pedagogical norms;

- I want to know if it’s possible to fail without being erased, cast out;

- I want to know what becomes possible when we stop thinking about education as a forward-moving, product-oriented march toward some mark of achievement, and instead we start thinking of it as something bent more towards chaos.

Carr goes on to propose six activities that can be introduced in the classroom to promote the pedagogy of failure:

- Failure Narrative. Provide students with an opportunity to “write about or discuss their impressions of and experiences with failure.” This exercise would allow students to “explore issues of success and failure in greater depth.”

- Failure Case Study. Students would identify and research a community, organization, culture, or individual that perceives or works with failure.

- Low-Stakes Writing Binge, or “Try Again, Fail Differently.” Students would work over a period of days or weeks on one topic or theme writing, editing, reworking consistently to work out how to say the same thing differently, or from a different perspective, or in fewer words. Carr suggests that this be supported with reflective journaling to see how/why the changes make the piece better, worse, or different and so that the students can witness how this process makes an emotional impact on them.

- Unlearning. Students should identify something they believe they are in an expert in and then “unlearn” it by identifying other ways one can become an expert which should lead to some understanding of the often arbitrary ways we learn and become experts.

- Novice Narrative. Students should identify something they’ve always wanted to learn, but never attempted and then spend weeks learning that thing. As they learn, they should keep a journal, blog, blog, or record in another way their progress and struggles of learning and recognizing the difficulty of failure.

- Assessing “Quality of Failure.” From Edward Burger’s “Teaching to Fail.” Burger provides his students with an opportunity to get an A grade in his course if they must demonstrate considerable failure by taking on and pursuing ideas in the coursework that may not seem safe. Students are then encouraged to share their failures more widely with the class leading to a universal “feltness” of failure with fellow students.

Lastly she goes on to remind us that these exercises are designed to allow the student to keep “tabs on one’s emotional proximity to one’s work and to the manner in which one’s work or one’s ways of knowing and doing work undergo change.” She suggests that work should allow for flexibility, improvisation, discomfort, restlessness, and causing notices. She claims that recognizing her failure has made her more inquisitive and become a more curious learner, less risk-averse, and more emotionally cognizant of the impact different kinds of work have on her. If we know our place in relation to our failures and triumphs, we will be better educators too.

As I said, Carr’s piece captivated me the most this week, but Brian Croxall and Quinn Warwick also provide some discussion of failure in the classroom. Mostly, they are looking at what happens in classrooms that engage with various forms of technology, but they recognize that the acceptance of failure in the classroom is a universal motivator both for the instructor and the students. The instructor would want to present material more effectively if they are not reaching their students. They present four “tiers” of failure and a real world case study is provided to illustrate each tier:

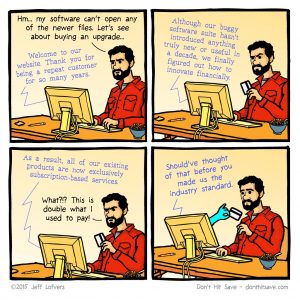

- “Technological Failure” – Technical glitches: whenever a technology is introduced in the classroom, there is a possibility of a glitch and the authors suggest having a contingency plan ready, but they also recognize that these types of tier one disruptions, although disruptive, provide opportunities for engaged learning where students see the instructor as fallible and that such obstructions can be overcome.

- “Human Failure” – Tools function, but students encounter difficulty using them or seeing how they will transform their understanding of a humanistic problem.

- “Failure as Artifact” – Students should seek out failure in their own work and learn from it

- “Failure as Epistemology” – Students should be actively encouraged to fail in their work and break the digital tools their tasked with engaging with.

I want to wrap up my post with one final list of the best practices (or “what I learned from things going wrong”) that I gleaned from the JITP readings, but what other practices have we identified this semester that can be added to this list? Further, can you foresee any failure in your pedagogical and academic process?

- Ask students how they want to learn. Open up the opportunity for them to contribute to the content of the course.

- Don’t provide too much guidance or structure to the point of inflexibility, but do provide enough context and assistance so that students can complete the work you are asking them to

- Don’t take on too many new things at once. Scaffold the work you are requiring and again, provide context when possible.

I hope that each of us will go back into our classrooms a little more invigorated and motivated by our successes AND failures, and that we will each continue to develop a caring, reflective, and critical pedagogical practice.

But first, we must make it through our final for ITP! 🙂

Also, if anyone is interested here are some more listening / reading pleasures:

- Audrey Watters provided an interview on the WET (Writing, Ed, Tech) podcast with Erik Marshall http://www.thewetpodcast.com/wet001-audrey-watters-educational-technology/ that goes into quite a bit of the failure theme from this week in addition to various other edtech thoughts.

- Hannah McGregor’s Secret Feminist Agenda podcast on failure (thank you, Maura, for the recommendation!): https://secretfeministagenda.com/2018/03/01/episode-2-7-playing-losing-failing/

- The Queer Art of Failure by Judith Halberstam (recommended by Hannah McGregor)

- The Importance of Failure by John Unsworth (recommended by Hannah McGregor)